Norm Pattis used to receive a hate letter once a year from an elderly woman in California. Incensed over a $2 million award the criminal defense lawyer had won for a convicted rapist and murderer injured by guards during a prison escape attempt, the woman would excoriate him and wish a painful death on him and his family.

Most people would be disturbed. Not Pattis. For him, the letters were a badge of honor. “I framed one of them,” Pattis says. “I figured if I was pissing off someone in California, I must be doing something right.”

It’s just what you’d expect from arguably Connecticut’s most colorful and controversial lawyer, defender of two of the most despised defendants in recent state history, accused wife murderer Fotis Dulos, who died in January after attempting suicide, and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, who has pushed the lie that the Sandy Hook school killings were a hoax.

“I’m 64 years old and I have a ponytail. I have issues with authority. If I take a case and it pisses off the other 7 billion people on the face of the Earth, that’s their problem, not mine.”

For more than 20 years, Pattis has roamed the state’s halls of justice looking for trouble. In that time, he’s been called everything from “attorney Slash and Burn” to “the P.T. Barnum of the courtroom.” Combative, whip smart, fast on his feet, provocative to the point of incendiary, Pattis specializes in cases that make most people cringe. He’s defended everyone from child murderers to rapists — he admits to being particularly drawn to homicide cases. If the allegation is heinous and the defendant reviled, chances are pretty good Pattis is involved.

But even for Pattis — who says he is attracted to chaos — this past year was a wild ride. On top of taking on Dulos and Jones as clients, he’s also seemingly declared war on the left, whose social causes he had long championed and fought for. In the past, he’s won cases for victims of sexual discrimination and racist harassment, as well as death-penalty appeals. But this past year he infuriated the New Haven NAACP, a former ally, by posting a racially charged meme on his Facebook page. The post depicted three hooded white beer bottles arrayed around a brown bottle hanging from a string. Its caption: “Ku Klux Coors.” Civil rights activists called it disgusting and racist. Pattis called it funny and free speech.

It wasn’t his only inflammatory social media post. He’s supported convicted rapist Bill Cosby and others. When newly elected Rep. Rashida Tlaib — the first Palestinian-American woman to serve in Congress — said on Twitter in January 2019 that she would “always speak truth to power,” Pattis replied, “No suicide bombing?” Asked about his tweet, Pattis says, “That was a flip expression of sarcasm, not more not less.”

The Facebook controversy seemed to have completed the transformation of Pattis — he’s also a public intellectual who often opines in columns and on his blog — from liberal fighter for social justice to Trump voter and right-wing critic of political correctness and so-called “woke” culture.

By year’s end it’s fair to say that Pattis was more famous — and reviled — than ever. He doesn’t care. “I like a fight,” Pattis says with a smile, sitting in the conference room of his cluttered, book-filled New Haven law office late last year. “I’m 64 years old and I have a ponytail. I have issues with authority. If I take a case and it pisses off the other 7 billion people on the face of the Earth, that’s their problem, not mine.”

Pattis’ critics and admirers don’t agree on much, but they do agree on one thing: He’s very good at what he does. He has the courtroom victories and hate mail to prove it. “He’s a natural-born trial lawyer,” says New Haven civil rights lawyer John Williams, Pattis’ legal mentor and former law partner. “He understands real people. That’s, of course, critical in dealing with juries. Then you add to that that he’s brilliant.”

But why has Pattis made a career of taking on such unlikeable clients? And how does a guy known for going after bad cops and racists defend a far-right conspiracy theorist?

He points to his difficult childhood, which left him with a burning desire to help people in their hour of need in contrast to how others did not help him when he needed it. “A good part of my vocation is wanting to bear witness and to make sure these [people] aren’t alone,” Pattis says. “I can provide that. They’re not alone in their worst moments.”

His other reason? He’s a fervent believer in free speech and deeply skeptical of the state, especially when it comes to its power to punish. “How is it that perfect strangers get to lock us up, put us in cages?” he says. “Do you really think that locking my client up for 60 years is going to make anything right or is it just going to make the world worse? And if you are going to do it, I’m going to make sure you do it right or it’s not going to happen at all.”

It’s not just Pattis’ representation of the likes of Dulos and Jones — lots of lawyers defend unpopular clients — that makes him such a lightning rod. Some lawyers stir the pot; Pattis tips it over and throws the contents at opponents. “I think there are things he does that attract a lot of lightning,” says William F. Dow III, a longtime New Haven trial lawyer. “He likes the scrum. He believes that once a lawyer signs on his obligation is to represent the guy to the fullest.”

Danbury State’s Attorney Stephen J. Sedensky III, who has crossed swords with Pattis in court, says: “He’s a very good lawyer, there’s no question about it. He’ll push the envelope in the courtroom, and he tries to push prosecutorial buttons.”

Pattis has done just that — to the extreme — in both the Dulos and Jones cases. He infuriated domestic violence victim advocates by positing that Jennifer Farber Dulos, who disappeared in May 2019, faked her own death or committed “revenge suicide” to frame Dulos for her murder à la the bestseller Gone Girl. That earned Pattis a stinging public rebuke from the novel’s author, Gillian Flynn, who said his theory “sickens” her. So aggressive was Pattis in his public statements that the prosecutor won a gag order against him, which Pattis sought to overturn at the state Supreme Court. Pattis provided further proof of his willingness to push boundaries after Dulos’ death by proposing his trial go forward with his estate as defendant in a bid to clear his name, a proceeding that would be unprecedented.

Jones, meanwhile, faces a lawsuit filed by families of the Sandy Hook victims alleging he and others defamed them by falsely claiming the shootings were a hoax to justify further gun control, subjecting them to ongoing harassment and threats. Pattis does not dispute that the Sandy Hook killings happened, but strongly defends his client’s First Amendment right to speak his mind, and denies Jones’ actions have hurt the families.

“[Pattis] broke our trust, and he kind of dismissed a group that really respected him and worked with him and thought he was a friend. He showed us otherwise.”

Most defense lawyers would stop there. Not Pattis. He has gone on Jones’ Infowars show and praised the Texas-based far-right talker as an honest man who believes what he says. Jones raises legitimate issues and should be listened to, Pattis says. “The Alex Jones I’m watching sitting with me is not a man filled with hate speech,” Pattis said during an appearance on Infowars last fall. “He is not a conspiracy theorist. He’s a guy who sits up nights worrying about how to connect random dots in our lives.”

Pattis has more than his share of critics who say he has gone too far and that his statements often cross the line. Hugh Keefe, one of New Haven’s most experienced trial lawyers, praises Pattis’ intelligence and legal skills, but says he is at times “gratuitously cruel.” Pattis, Keefe says, “sometimes seems to be fighting something inside.”

When asked if Pattis crosses lines, Keefe says: “There’s no doubt about it. If he treated people less cruelly, especially when he wrote columns, he would really break through the door into that group of elite, very select lawyers.”

In response, Pattis says that he’s unsure what Keefe means by an “elite, very select” group of lawyers. “I take the cases that come my way and do what I can with them,” he says. “I know I am far from perfect. The law is a very cruel profession.”

And the dust-up over the social media post condemned as racist? Pattis remains unrepentant. He denies the meme was racist and says he posted it to make a point about free speech. He also thought it was funny, which he acknowledges shows he has “a blind spot.” Angered by the NAACP’s response, he has ended his longstanding partnership with the group. “I’d be willing to bet I’ve done more for people of color than you have and you are on the board,” Pattis recalls telling a local NAACP official. “Next time you need a pro bono case, lose my number.”

Nearly a year later, New Haven NAACP President Dori Dumas was still seething. “It was disgusting,” says Dumas, who explored going after Pattis’ law license over the incident. “We expected more from him. It’s more than disappointing because he broke our trust, and he kind of dismissed a group that really respected him and worked with him and thought he was a friend. He showed us otherwise.”

But behind the hardball tactics, ferocious reputation and slashing rhetoric, another side of Pattis lurks. He’s a deep thinker who devours books in a constant quest for enlightenment and self-improvement. His idea of Disneyland is attending the annual Hay Festival of Ideas in Wales, which has been described as “the Woodstock of the Mind.” Get into a serious conversation with Pattis, and he will bounce from philosopher to philosopher as casually as some men bounce from ballplayer to ballplayer. During an interview for this article, Pattis quoted or referenced thinker Immanuel Kant, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, St. Augustine, the New Testament, Machiavelli and Kurt Vonnegut all in one 3-minute stretch.

“He is one of the best-read people I’ve ever known in any field,” Dow says. “And he remembers everything he reads. He’s reading stuff to learn, to expand his mind, to test himself.”

Pattis was born in Chicago in 1955 to a mother of French-Canadian descent and a father who had emigrated from the Greek island of Crete. One day when Pattis was 6 or 7, his father left the house and never came back. Pattis says that the abandonment haunts him to this day.

Years later, in his 40s, Pattis reconnected with his dad, who told him he had been a career criminal in Detroit specializing in payroll heists and fled to Chicago after shooting a man. “It was like talking to Sam Spade,” Pattis says, referring to the hard-boiled private detective in The Maltese Falcon. Pattis’ father eventually went straight, remarrying and settling in Virginia where he developed homes for troubled teenagers, even winning an award from the state for his work. “I remember thinking I could have used some of that attention when I was a kid,” Pattis says.

Mother and son returned to her native Detroit where they struggled on the edge of poverty. They moved constantly, at one point living in an unfinished attic. Things went from bad to worse around the time Pattis went to high school when his mother took up with a violent alcoholic who detested him. Pattis suddenly found himself unwelcome in his own home and would only return after his mother and the man went to bed. At one point, he tried sleeping in the woods, only to get extremely sick.

It is those two traumatizing experiences — abandonment and being unwelcome and loathed in his own home — that drive him, Pattis says. He understands what it’s like to be hated and forsaken, giving him empathy for the accused who are reviled and the downtrodden, and he’s driven to come to their aid.

He nonetheless struggles at times to understand why he’s so attracted to heinous cases — he cites his decision to defend Tony Moreno, who was convicted of throwing his baby off a Middletown bridge in 2015, as an example — and has spent the last decade in psychoanalysis searching for answers. It’s part reliving the trauma of his childhood, part a desire to be there for people in trouble as virtually no one was for him, part pride, but there’s another element, he says: grace, the Catholic idea of a gift received without asking.

“I think I’m an instrument of grace for others,” he says. “What in these cases the families are looking for is someone to recognize the humanity of their loved ones and to stand beside them when the world hates them. If I can be that voice to say, I understand, or that voice that says to the state, not so fast, or the voice that says to the judge, consider this, that’s pretty cool. That’s enough for me.”

Pattis’ moment of grace — what saved him — was his mother’s decision to get him involved in Big Brothers. His big brother came from Grosse Pointe, a tony Detroit suburb, and introduced him to a world he never knew existed. His influence and a vice principal’s encouragement and help propelled him to college after he graduated early from high school. He eventually landed at Purdue University in Indiana where he earned a degree in political science.

“What in these cases the families are looking for is someone to recognize the humanity of their loved ones and to stand beside them when the world hates them. If I can be that voice to say, I understand, or that voice that says to the state, not so fast, or the voice that says to the judge, consider this, that’s pretty cool. That’s enough for me.”

But Pattis didn’t go right to work after graduation. From an early age, Pattis says he has felt a burning desire “to know God.” To that end, he spent time in Switzerland at the compound of an American Christian fundamentalist thinker named Francis Schaeffer and then found himself in the graduate philosophy program of Columbia University, where he studied and taught for six years. At one point, he nearly joined the CIA, but that opportunity fizzled when the agency didn’t like his polygraph answers about homosexual experiences. “I said, ‘Well, I haven’t had any yet. I don’t know how I’m going to respond to my midlife crisis,’ ” he recalls. “I think they decided that was a little too much for them.”

Unhappy teaching, struggling to finish his dissertation, Pattis decided to try something new and landed a job in the mid-1980s writing editorials for the Waterbury Republican-American newspaper. Next stops were the Hartford Courant editorial page and then spokesman for the Connecticut Hospital Association, with a brief detour working on New Haven developer Joel Schiavone’s 1990 gubernatorial campaign. None of it was satisfying. Deep into his 30s, Pattis found himself at sea once again. He decided to try the law.

“I felt I wasn’t having an impact on the world around me,” he says. “I thought, I don’t want to be sitting ringside. I want to get in, and so at a minimum if I go to law school, I’ll learn how the law works.”

After graduating from UConn law school, he went to work for civil rights attorney John Williams and almost instantly discovered his oeuvre. Fellow New Haven trial lawyer Richard Silverstein recalls him bursting onto the local legal scene like a comet. “I’ve never seen a lawyer hit the ground running like him,” Silverstein says. “In two or three years, he made a name for himself.”

Nearly 40, the poor kid without a father from the wrong side of the tracks had finally found his place in the world.

It’s a Monday afternoon in early November, and Pattis is prowling his natural habitat, the New Haven County Courthouse at the corner of Elm and Church streets just across from the Green. Pattis is there to defend yet another in his large stable of criminal clients, New Haven police Lt. Rahgue Tennant. In 2018, the veteran police officer allegedly barricaded himself, his wife and his children inside their home for several days during which time police say he assaulted his wife.

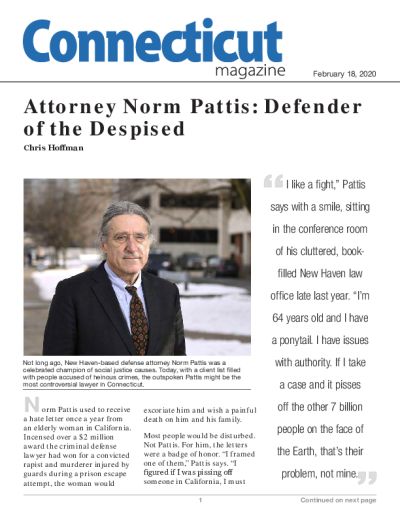

Dressed in a rumpled dark pinstriped suit, white shirt, purple tie and running shoes, his wiry, gray-streaked hair pulled back into a foot-long ponytail, Pattis bounds into the courtroom with the vigor of a man half his age. The running shoes aren’t just for show. An avid runner, Pattis is training for a half-marathon, he says.

Pattis explains that he has just emerged from a negotiating session with the prosecutor — “stuffing sausage,” he calls it. Settling his six-foot frame onto a bench to wait for the judge to enter, he looks as comfortable and at home as a man easing into his recliner in his living room. “You can get the nolle stamp out right here,” he jokes to the prosecutor as she walks by, using the legal term for the prosecution dropping the case. She smiles.

While the Jones and Dulos cases get the most attention, lower-profile criminal cases like this one, along with representing state employees who get in trouble at work, are his bread and butter, Pattis says later. People think defense attorneys make a lot of money, and while he earns a good living, Connecticut isn’t New York or Los Angeles, he says. In fact, high-profile cases are, if anything, a drag because they consume so much time and energy, he says. “I sometimes think I should have fallen in love with personal injury or bankruptcy law,” he quips.

Tennant leaves his family seated on benches and comes over to consult with Pattis. “Let me be the lawyer and you be the client,” Pattis tells him at one point in a firm but gentle voice. After a few minutes of hushed conversation, Tennant returns to his family. The bottom line: Pattis has negotiated a deal under which Tennant will plead guilty to misdemeanors and get a suspended sentence, but Tennant has decided not to take it and instead go to trial.

“I’m not sure that I’d know justice if it bit me in the ass,” Pattis replies. “I’m not sure if I believe in a just society. I’m less interested in an equalitarian or egalitarian society than I am in respect for persons.”

Trials are what Pattis does best, what he loves — he’s litigated more than 150 — but he knows they are unpredictable. He likens his clients’ situations to being tied to the railroad tracks as a speeding freight train bears down on them. His goal is to either stop the train or get them off the tracks, he says. “I have no idea how a jury comes to a decision,” he says. “My job is to get as much of you out of this courtroom as I can.”

It is at those trials that some say Pattis sometimes goes too far, such as the case of Yale student Saifullah Khan, whose acquittal on a rape charge Pattis won in 2018. During the trial, Pattis subjected Khan’s accuser and fellow Yale student to a relentless grilling that left her in tears, at one point pressing her on why she wore a black cat Halloween costume instead of “a Cinderella in a long flowing gown” outfit on the night in question.

“The tactics he was using in this case crossed the line,” says Laura Palumbo, communications director for the Pennsylvania-based National Sexual Violence Resource Center. “To me that comment is an attempt to smear the plaintiff’s character and to suggest that by not choosing an outfit for Cinderella in a long-flowing gown, that she’s a slut.”

Pattis declined to comment on her criticism.

In the Tennant case, the judge finally enters the courtroom. Pattis, Tennant and the prosecutor stand at the table in front of her. After learning that Tennant wants to reject the plea deal, the judge asks him a series of standard questions to ensure he fully understands and has thought through his decision. When she asks Tennant if he’s had enough time, he announces he hasn’t. He wants to mull over the offer some more. The judge agrees to let the deal stand while he does so.

Afterward, outside in the hallway, Tennant and Pattis talk for a few minutes as his family waits on a nearby bench. (Tennant later chose to go to trial.) After they finish, Pattis walks over and points out a mosaic on the soaring ceiling at the far end of the building depicting a classical scene. One of the female figures in the mosaic has an exposed breast, he notes. “If she walked in here like that, they’d arrest her,” Pattis says with a wry smile. Just another example of the hypocrisy of the system, he observes, as we head for the exit.

Later, in his nearby law office, Pattis talks of his transformation from left-wing darling to liberal bête noire. What happened? Has he changed? It’s something he says he asks himself. He downplays his social justice work. His cases included a $1.5 million award in a sexual discrimination case against the New Haven Fire Department and $37,500 for a Norwalk High School student subjected to racist messages on her phone, as well as a number of high-profile death penalty appeals. “I fight for people,” he says. “I don’t fight for causes.” He points to what he views as the left’s retreat from the First Amendment, reasoned argument and pluralism in favor of tribal politics in which only certain ideas are acceptable and white males must defer to historically marginalized groups.

Pattis is particularly scornful of the concept of white privilege, which he views as a cudgel to extract reparations from whites and stifle their speech. Pattis hasn’t always felt that way, or at least hasn’t always said such things. At a 2012 rally protesting the verdict in the Trayvon Martin case, he opened by asking an adoring and mostly minority audience, “Anybody doubt that if George Zimmerman put a bullet in my chest he’d be behind bars right now?” Later in his speech, as he pinched his cheek, he said, “I got a passport in this life to enjoy the good things in life without working for it. You’re looking at it.”

Reminded of the rally, he acknowledges he has changed his tune. Could it be that he got cold feet when activists began demanding action instead of just words? “Possibly,” he says. “It has more to do with being a misanthrope.” Like one of his heroes, the 18th-century Scottish philosopher David Hume, about whom he wrote his unfinished dissertation, he’s deeply skeptical of humanity and any ideologies that claim to have all the answers.

But what of the ideal of justice, of a just society? Hasn’t Pattis devoted his life to the pursuit of justice? That’s not how Pattis views it. “I’m not sure that I’d know justice if it bit me in the ass,” Pattis replies. “I’m not sure if I believe in a just society. I’m less interested in an equalitarian or egalitarian society than I am in respect for persons.”

“I believe in original sin. I’m a sinner in need of grace. We all are.”

In the end, free speech — no matter how odious — is paramount, Pattis says. That’s his reason for defending Alex Jones, whom he has come to genuinely like and respect. Jones’ ideas may be wacky at times, but he has a right to say them, Pattis says. “Donald Trump didn’t steal the election. Alex Jones doesn’t make people watch him. The critical question is, what makes them possible? There’s a legitimacy crisis in the United States. We no longer share common values, and people are looking for answers.”

To the Sandy Hook families, his message is simple: What happened to you is awful. But Alex Jones did not defame you, and he has a constitutional right to say what he wishes. “Everyone suffers loss in life,” he says. “It’s been seven years. It’s horrible. Move on.” (Koskoff, Koskoff & Bieder, the law firm representing the families in their suit against Jones, did not return a call seeking comment.)

To Pattis, the true villains of American life, the greatest threats to the republic, are not Jones and Donald Trump, but Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook. He blasts the social media site and its founder for suppression of free speech, massive invasions of privacy and “surveillance capitalism” — the exploitation for profit of users’ data without their permission or knowledge. He says he is preparing a lawsuit challenging Facebook’s deplatforming of Jones on First Amendment grounds, a case he acknowledges is likely to fail. It’s a fight worth having, he says.

Throughout the conversation, Pattis keeps returning to his lifelong quest to know God and how that quest infuses his life and work. As a child, he sometimes attended Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches before his flirtation with Christian fundamentalism as a young man. More recently, he is drawn to Catholic theology, reading and rereading the catechism and especially the works of St. Augustine. “I’m an Augustan,” he says. “I believe in original sin. I’m a sinner in need of grace. We all are.”

Pattis’ passions aside from the law are running and books — he consumes two to four a week on top of his heavy workload — and they clutter his home as well as his law office, he says. “It’s my drug,” he says. He’s a collector of antiquarian books and with his wife owns a bookstore, Whitlock’s Book Barn in Bethany. Pattis delights in showing off some of his prized volumes, including a rare book from the 17th century, early 19th-century volumes whose page edges form colorful images when fanned, and a book signed by the crusading early-20th-century lawyer Clarence Darrow, another of his heroes. Darrow’s photograph hangs in his law office along with pictures of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Pattis hopes to one day soon devote more time to his beloved books, his wife, his three grown children, the large property where he lives and writing. He doesn’t intend to do what he does too much longer. Part of him still can’t believe he made it this far. “I’m in the home stretch,” he says. “I like to say I’m rounding third and headed for home.”